Why does medieval art look so strange?

To put it another way, why does the style of medieval art looks so different from the Renaissance style that followed it? Medieval paintings, with their cartoon-like faces, surreal proportions, and backgrounds of pure gold, appear to portray a different world than the naturalistic works of the Renaissance.

For instance, consider the painting style of the Rochester Bestiary, circa 1230. The following painting depicts the Genesis story of Adam naming the animals.

It’s as though the artist had never seen a real lion before, or a real donkey, or even real grass. The portrayal of the lion may be forgivable, but medievals had definitely seen donkeys and grass! Yet, these animals have cartoonish, anthropomorphic faces and the ground looks like gelatin.1

In a painting of the same story from the Aberdeen Bestiary, circa 1200, the manuscript is structured more like a comic book, with a similarly fantastical painting style. As in the Rochester Bestiary, the animals look more like heraldic symbols than realistic three-dimensional figures. In both of these bestiaries, the individual objects and places are generally recognizable, but the depiction of neither landscapes nor living things seem to imitate the three-dimensional physical world.

Even the most ornate works of the Middle Ages look markedly two-dimensional compared to the Renaissance paintings of just a couple centuries later. For instance, in medieval paintings of the Virgin and Child, there is a low level of spatial depth, and the infant Jesus is frequently depicted with adult-like proportions. By comparison, Renaissance paintings of the same subject appear to take place in a three-dimensional world, with elaborate backgrounds and naturalistically proportioned figures.

The default style

The art of the Middle Ages is not the only type of art to employ this type of two-dimensional style. The geometric depth of Renaissance painting is really the exception to the historical norm. The ancient painter, whether a Bronze Age Egyptian, Vakataka Indian, or Minoan Greek, seemed to view painting as a matter of representing two-dimensional figures.

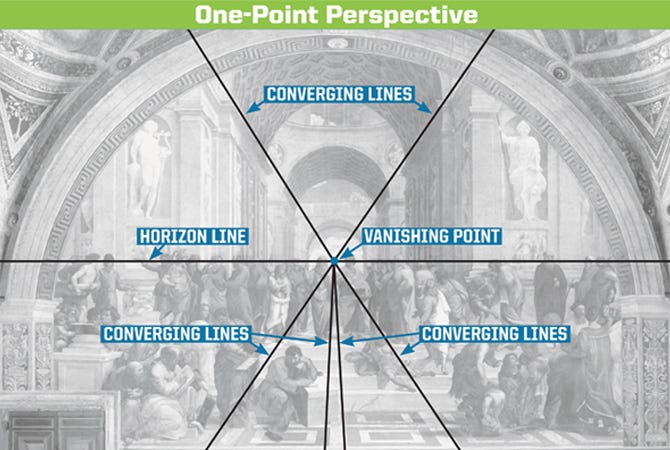

There were suggestions of three-dimensional space in the fresco paintings of late Rome and the ink paintings of imperial China, but it was not until the Renaissance that paintings achieved consistent, three-dimensional proportions.2 The geometric system of linear perspective, discovered by Florentine architect Filippo Brunelleschi around 1415, fully added the third dimension of depth.

Linear perspective is a technique which simulates the appearance of three dimensions on a two-dimensional surface. The impression of depth is created by the convergence of parallel lines at a vanishing point. Objects nearer the vanishing point appear smaller, and those farther from the vanishing point appear larger. The diminishing appearance of objects as they recede into the distance is known as foreshortening. This system provided artists with the geometric precision to paint a mirror image of the natural world.

The concept of linear perspective is simple, at least in hindsight. The development of this system resulted in an unprecedented level of naturalism during the Renaissance. But why didn’t artists paint in three dimensions before? What was the appeal of that older, highly symbolized style of painting?

Symbolic style

Before painters represented scenes in three-dimensions, they painted in symbols.

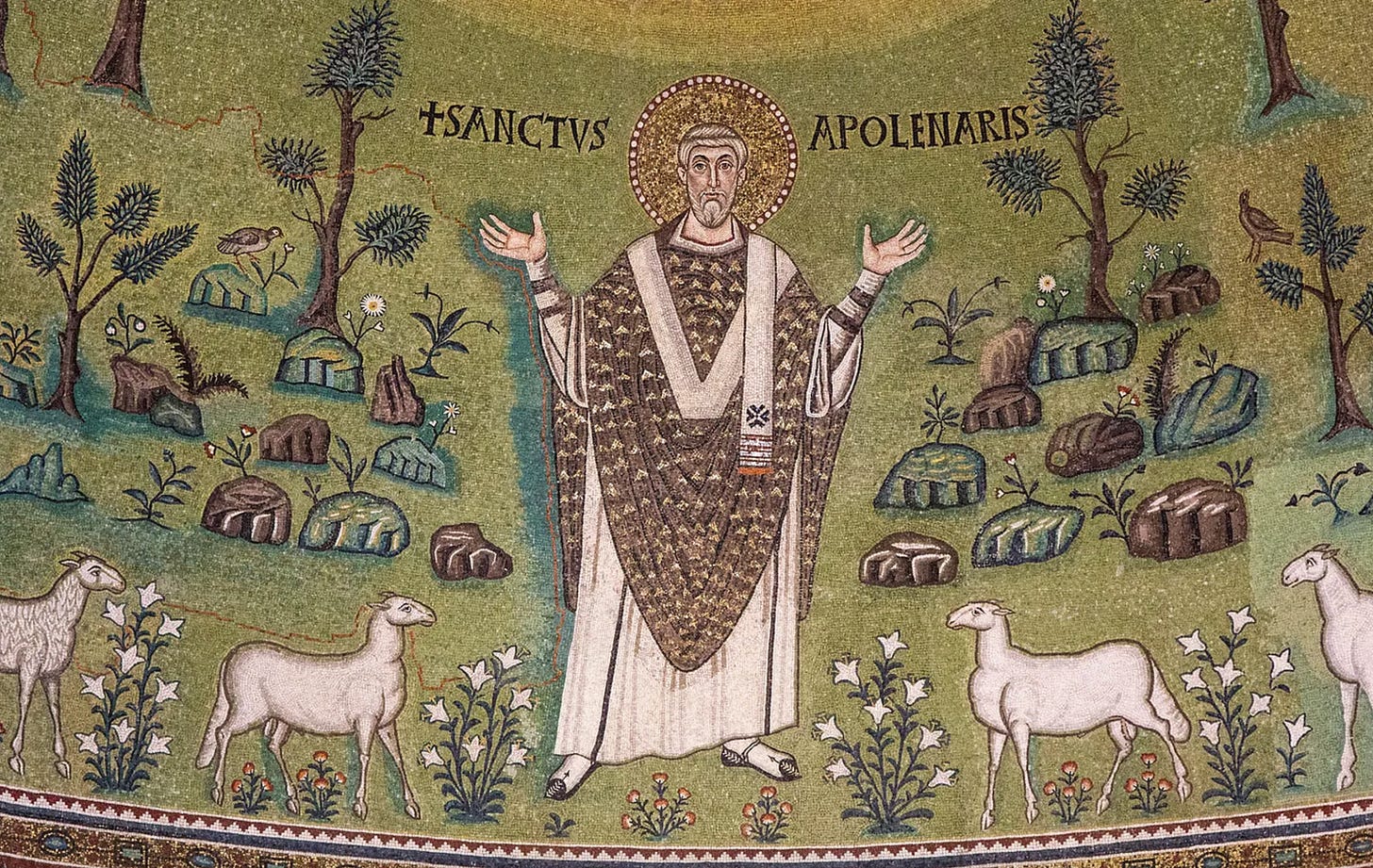

While paintings before linear perspective contain height and width, they broadly lack the third dimension of depth. As a result, scenes in these paintings tend to not look like earthly, physical places. Objects are located on a symbolic plane where their placement tends to serve a figurative purpose rather than a literal imitation of physical space. This is why, for instance, the medieval baby Jesus is often depicted with an adult form. From the perspective of the medieval eye, the baby Jesus — a perfect, unchanging humunculus — merited a mature appearance.3

In this style of composition, which I’ll broadly call symbolic style, a painting’s physical place is subordinate to its narrative elements. In contrast to the naturalistic style of the Renaissance, which represents the physical world in three dimensions, symbolic style relies on non-literal techniques to convey meaning. These techniques do not represent the physical world as it looks, but prioritize the presentation of meaningful symbols.

A common technique used in symbolic style is scaling people and objects according to their symbolic importance. This technique, sometimes known as hierarchical perspective, is employed in the ancient Egyptian fresco below. The painting depicts the slaves as being about half the size of the high-ranking government official and his family members. As a viewer, the hierarchical perspective of the painting has the effect of instantaneously drawing your attention to the high-ranking figures.

Another notable feature of the Egyptian fresco is that there is little overlap between individual objects. The birds and fish are mostly separated in space and individually outlined. The boat isn’t really in the water, but floating slightly above it. Meanwhile, the woman in the upper-left isn’t seated on anything in particular, but looks to be essentially levitating. Instead of painting one object in front of another, the artist expressed depth vertically — objects that are farther away appear above objects that are closer. This technique, sometimes called vertical perspective, is an alternative to linear perspective for conveying depth. It’s comparable to a loosely-arranged grid in which more distant objects are positioned higher in a vertical column. Vertical perspective allows an artist to fully display individual objects, without the inconvenience of one object obscuring another.

Another defining quality of symbolic style is the role of non-literal backgrounds. In symbolic style, little attention is paid to the details in the distant backdrop of a scene. Instead of filling the background with elaborate landscapes and architectural structures, an artist would opt for solid colors or abstract decorative patterns, or simply leaves the background blank.

When comparing the backgrounds of a medieval and Renaissance depiction of the Crucifixion, this contrast is stark. In the French medieval painting on the left, the background consists of blue and orange abstract, ornamental patterns. The foreground includes objects from both the visible and invisible worlds — angels appear in the sky, and each figure in the painting wears a halo, except for a downsized Adam, who collects the blood of Christ in a goblet. Meanwhile, the Renaissance painting on the right does not feature the invisible world at all. Instead, the painting portrays a meticulously detailed visible world, including an elaborate landscape that extends far into the distance.

Landscapes are uncommon in symbolic style. Rather than portraying remote details of the natural world, artists often styled their paintings with flat, but symbolically expressive backgrounds. For instance, medieval Christian artists often used a leaf of pure gold for the background of a religious narrative. The noble metal emphasized that the events took place on a spiritual plane, transcending the physical world.

In the following medieval Christian manuscript on the left, the resurrected Christ is depicted in front of an ethereal sheet of gold. Meanwhile, the relatively miniature Roman soldiers are set against the comparatively dim and earthly backdrop of the tomb. Compare this with the image on the right, an early Flemish Renaissance painting — the height of the risen Christ matches that of the Roman soldiers, and the background is a lifelike landscape, evocative of the outskirts of a Dutch city. The medieval painting highlights Christ’s spiritual glory, while the Renaissance painting emphasizes his physical incarnation.

Is art like human vision?

Why does symbolic style hold sway throughout most of history? On one hand, symbolic style seems very different from the way that the human eye sees. There is little indication of depth, preventing the viewer from using the size of objects to gauge distance. It’s as if the scene is not viewed from human eyes, but in an abstract world in which objects do not follow physical laws.

In another respect, symbolic style shares some interesting features with human perception. When we see a scene, we’re not focusing on each object equally, but we pay most attention to what seems most relevant. If you’re fishing, you’re probably not focusing on the marshes in the distance or the subtle shadows cast by the boat. Instead, you’re thinking in terms of relevant concepts — bait, boat, fish, rod, water.

Our eyes don’t focus equally on each ray of light that enters our vision. We perceive visual information with highest resolution in the foveal center, with declining sharpness toward the periphery. Our eyes constantly change focus, darting around in pursuit of psychological salience.4

And similarly, to the medieval mind, the mounds of dirt and patches of grass far from the location of the Cross were totally trivial in scenes as spiritually significant as the Crucifixion or the Resurrection. Instead, artists emphasized the objects that would capture the focus of a pious observer. Even invisible objects, like angels and haloes, were more important to the symbolic narrative than an accurate portrayal of the geography of Golgotha.

You could think of these symbolic artistic techniques as a specific vocabulary of symbols. If you aren’t familiar with the symbols, the painting may look incomplete and slightly confusing. It may seem comical, with absurdly-sized babies and people floating in the air. Yet, to a viewer conversant with the artistic vocabulary of a particular time and place, symbolic style can express a wide range of concepts without naturalism.

Two ways to illustrate vision

Symbolic style and naturalistic style are two different ways of illustrating vision.5

Symbolic style is a representation of the subjective, phenomenal experience of vision. Not all concrete visual content is portrayed in the painting — only what is understood to be important enough to capture the viewer’s attention. Figures are not represented with detached geometric precision — like the reflection of an inanimate mirror — but influenced by subjective, qualitative impressions. Scale and order are determined by symbolic significance rather than how matter literally occupies space.

In contrast, naturalistic style represents the concrete physical world in an objective and fixed manner. Geometric shapes are strictly translated from the three-dimensional world onto a two dimensional plane. There is no selective focus and no overt psychological filtering. There is only the world as it concretely appears from a particular vantage point. This is the world that Renaissance artists wanted to portray — a mirror image of the physical world.

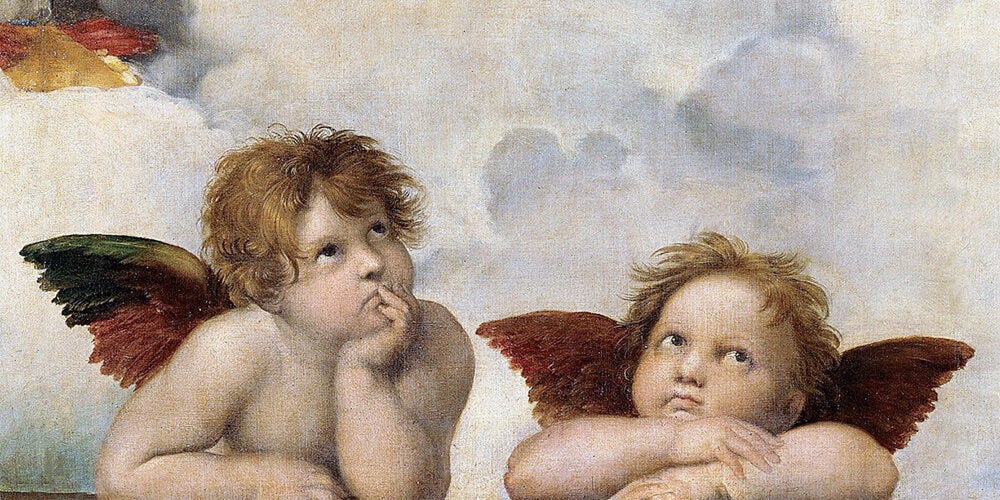

This doesn’t mean that naturalistic art cannot use symbols or represent the supernatural. Rather, the depiction of symbols is constrained by consistency in portraying light, shadow, and three-dimensional space. The artist still crafts the composition of the painting, but it takes place in the geometrically consistent physical world. For example, Raphael’s paintings still had cherubim and the glory of God — they just looked three-dimensional!

How things look

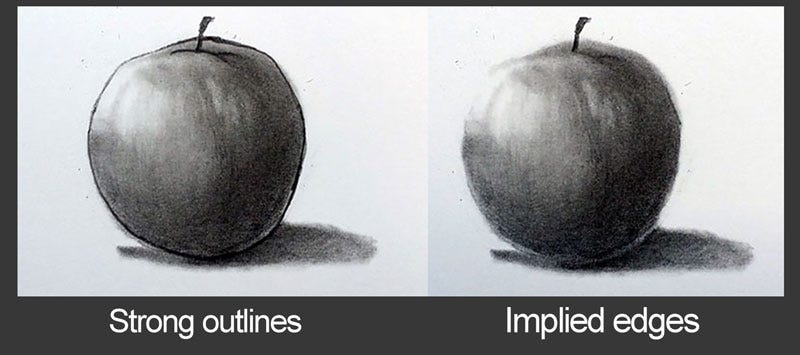

In order to paint naturalistically, an artist needs to set aside abstract impressions of things and just represent how things really look. This is why learning to make naturalistic art is not that intuitive! When most people learn to draw, their drawings look unnatural in predictable ways. For example, drawings of people tend to have oversized heads and objects look excessively outlined.

Maybe we draw heads too large because heads and faces are particularly strong attractors of human attention. But in order to draw naturalistically, we have to pause thinking about the idea of the human form, and just portray how it looks. The ratio of an adult head compared to the whole body — about 1 to 8 — is usually smaller than how it is depicted by novice artists.

Similarly, real clouds just look like overlapping white-ish puffs, dabbled sporadically across the sky. But when we think of clouds, we think of individual, abstract things, and new artists tends to draw them as distinct, outlined shapes. Our mind wants to think, these are separate clouds, so I will draw them as distinct, outlined shapes! but they really just look like white-ish puffs. So, naturalistic art requires detachment from conceptual ideas of how the world should look. A artist pursuing naturalistic style should simply observe the visual field, with its many smears of colors, blending into each other to varying degrees.

For instance, in the following drawings of an apple, the apple on the left appears relatively cartoonish because it looks like the concept of an apple — distinct and abstracted from its background. But real apples aren’t outlined. The drawing on the right has a naturalistic appearance because the apple is not isolated from its background. The shiny, white edge of the apple blends into the white background. The appearance of a real apple is not the concept of an apple, but a splashing of different hues, which sometimes blend into other things.

In summary, medieval art looks like the mind conceptualizing the world through medieval symbols. This makes it look more like cartoons than photography. This is the more intuitive, spontaneous way to create art, since our way of understanding the world is thoroughly informed by symbols and concepts. Medieval art freely fills space with symbols, without concern for geometric accuracy. This symbolic style allows the artist to represent whatever subjective perception comes to mind, filtering out noise within the physical world and focusing on important concepts.

A dramatic change occurred during the Renaissance. Symbols, even religious symbols, developed a third dimension. Renaissance artists invited viewers to gaze around a painting and orient their vision within a canvas of projected three-dimensional space. Renaissance artists continued the medieval expression of symbolism, but the symbols existed in a measured, geometrically consistent world.

The scene takes place after God invented soil and vegetation in Eden, so we should assume that the undulating ground is meant to represent a field.

Late Roman frescoes indicate an awareness of the idea of a vanishing point, but the vanishing points themselves are inconsistent. Imperial Chinese paintings from at least the Eastern Han Dynasty use oblique perspective, which has a geometric structure but does not use vanishing points.

You may wonder if that they painted babies like adults because they didn’t know how to paint baby proportions. It’s possible, and medieval artists definitely didn’t have a model of a Vitruvian Baby. However, some Virgin and Child paintings show the baby Jesus with male pattern baldness, which suggests that the decision was intentional.

Some paintings have played with blur to imitate foveal vision, which is an interesting interpretation of optical naturalism.

Paintings like Giotto’s Adoration of the Magi (circa 1320) exemplify the transitional period between these two styles.