Why did linear perspective develop in Renaissance Florence?

Notes on the history of linear perspective: part 2

This essay is the second part in a series about linear perspective. Part 1 can be found here.

What can you learn about a culture through its art?

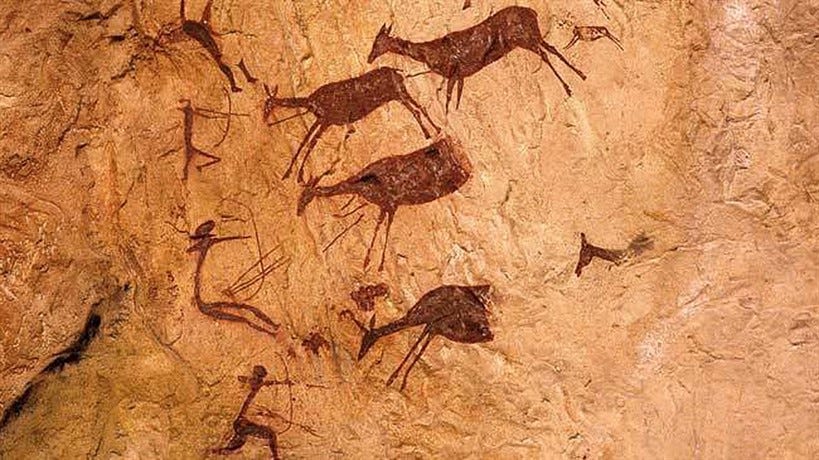

For instance, a Paleolithic cave painting is more than just a pretty picture. It may tell us which animals a group of people were familiar with, what materials they had at their disposal, or at the very least, which kinds of situations they thought were interesting.

It’s not a perfect science, but if a culture changes its style of art, it’s probably pointing at a greater cultural change. If a society’s aesthetics change, what else might have changed? Their economy? Their beliefs? Their rulers?

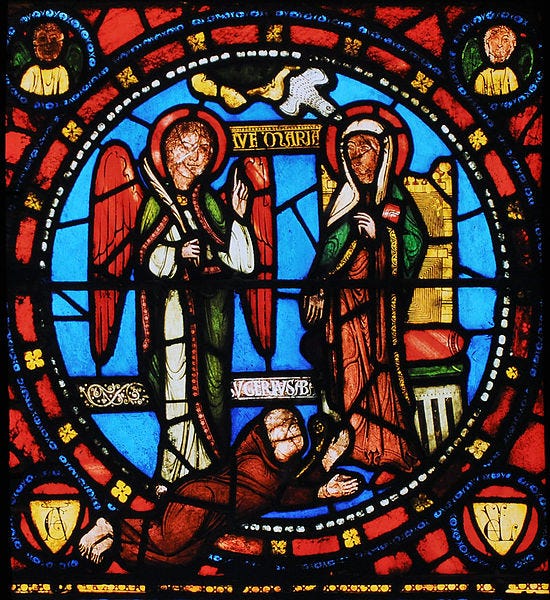

One of the most noticeable shifts in the history of art took place during the transition from the western Middle Ages to the Renaissance. This change was largely led by Florence, where painters left behind the symbolic, otherworldly style of the Middle Ages and began concrete imitating the world around them.

We can see this change in the way that Florentines depicted their own city. For instance, below is an anonymous Florentine painting from the late Middle Ages. The painting looks like Florence, with its characteristic sandstone walls and bright terracotta roofs, but it doesn’t look like any particular view of the city. It looks more like a visual summary of the entire city. The painting looks like its creator stitched together views from many different angles and perspectives of Florence, rather than closely imitating one specific vantage point.

Compare that to a painting of Florence from two centuries later. In the anonymous painting below, the artist portrays a particular area in Florence — the Piazza della Signoria. The arrangement of buildings aligns with how the city could look in person — you can imagine there is a specific point in Renaissance Florence that would recreate this exact view. The buildings appear to linearly decrease in size as they grow farther from the viewer, emphasized by the straight, neat gridlines on the ground. The artist here used the Renaissance invention of linear perspective, which gave artists a systematic guide to consistently imitate the shapes of the physical world.

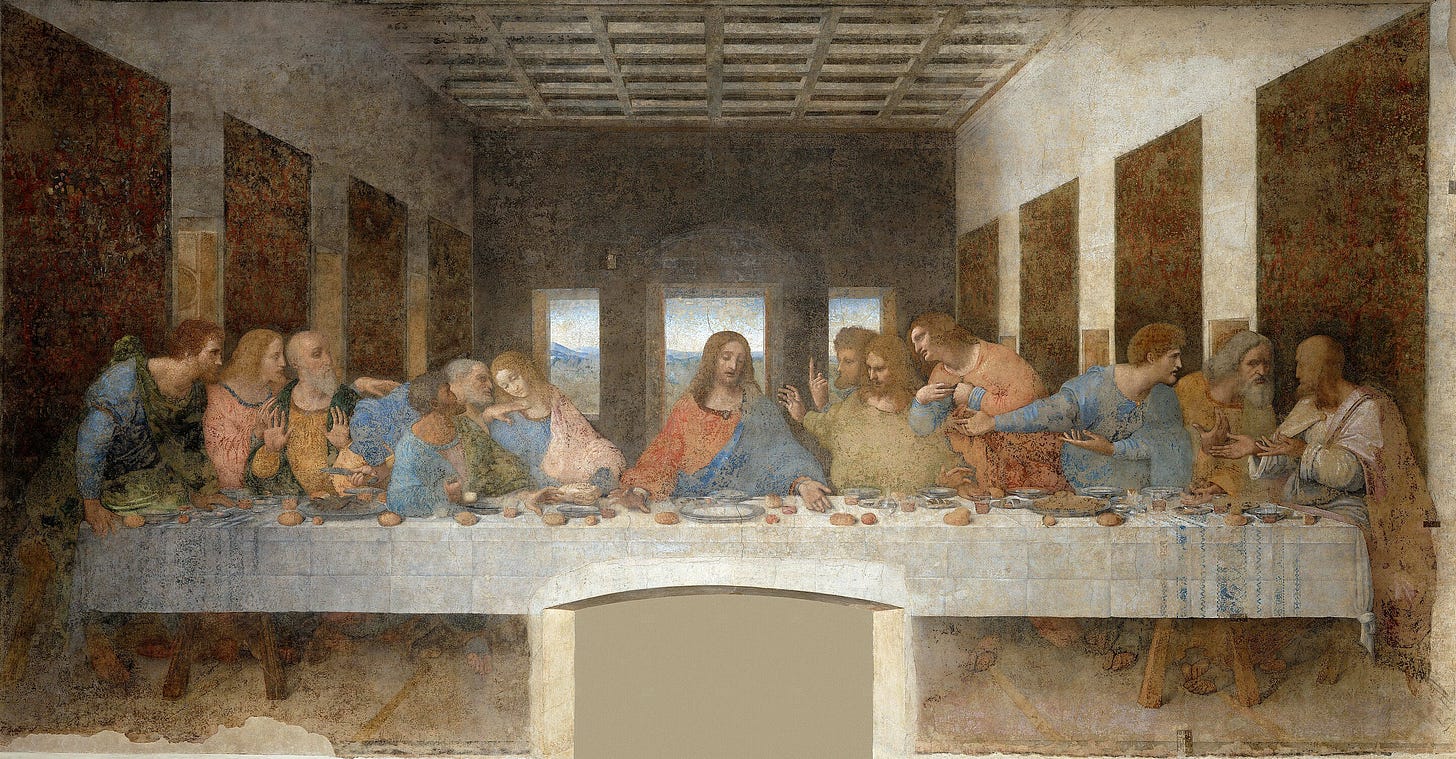

Now, what is the point of art? Is it to communicate a subjective impression of experiences and concepts, or to concretely represent physical space? Opinions differ, but Renaissance Florentines were devoted to the latter view. The Renaissance painting of the Piazza della Signoria was created within a Florentine tradition of linear perspective that originated in the early fifteenth century with Filippo Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti, and later refined by the likes of Leonardo, Michaelangelo, and Botticelli. Linear perspective was a Renaissance tool for a new kind of art which methodically depicted space from the concrete perspective of a human observer.

So, why Florence? And why during the Renaissance? Not unlike ancient Athens, 15th century Florence was a city of a couple hundred thousand people that punched well above its weight in cultural influence.1 Why did Florentine artists innovate so much in such a short period?

The Measured City

I previously discussed how linear perspective built upon Euclidian geometry, which was reintroduced in Western Europe during the late Middle Ages. Before the Renaissance, Giotto and other late medieval artists experimented with three-dimensional shapes, but they were not depicted with a consistent vanishing point. These shapes were eyeballed rather than measured.

Ultimately, linear perspective developed when artists discovered a way to portray three-dimensional shapes consistently on a canvas. Brunelleschi is credited with creating the first perspective painting using a grid, and Alberti used evenly-spaced vertical and horizontal coordinates in his 1435 linear perspective manual. But where did this idea — previously absent from medieval thought — of painting with a grid come from?

While the Cartesian coordinate system as we know it was not invented until the 17th century, it was long proceeded by the practical use of grids. Grid layouts for cities have existed at least as far back as the Bronze Age.2 Florence itself was originally built as a military encampment in the Roman Republic, and its original grid-pattern can be seen today in the layout of the city center.3

Other than the grid layout underneath Florentines’ feet, grids also appear in the works of Renaissance Florentine land surveyors and architects.4 Alberti had personal experience with land surveying before he wrote his perspective manual. In the early 1430s, he wrote a surveying manual for creating a scaled representation of Rome. This general interest in mapping physical space with a scaled coordinate system would be realized again in his perspective manual.5

Cartography

Alberti’s representation of Rome was a notable departure from medieval approaches to mapmaking.

For comparison, early medieval European maps were not to scale, and they probably weren’t meant to be. For example, the Psalter world map shown below looks more like a fantasy treasure map than a modern atlas. The map centers around a circular representation of Jerusalem, with sacrosanct sites exaggerated in size, not unlike the hierarchical perspective style found in medieval art. Parts of the map are filled with nebulous here be dragons imagery, like the depiction of monstrous people on the map’s right edge. This map, along with most maps of the medieval West, were far more concerned with allegorical abstractions than practical navigation.

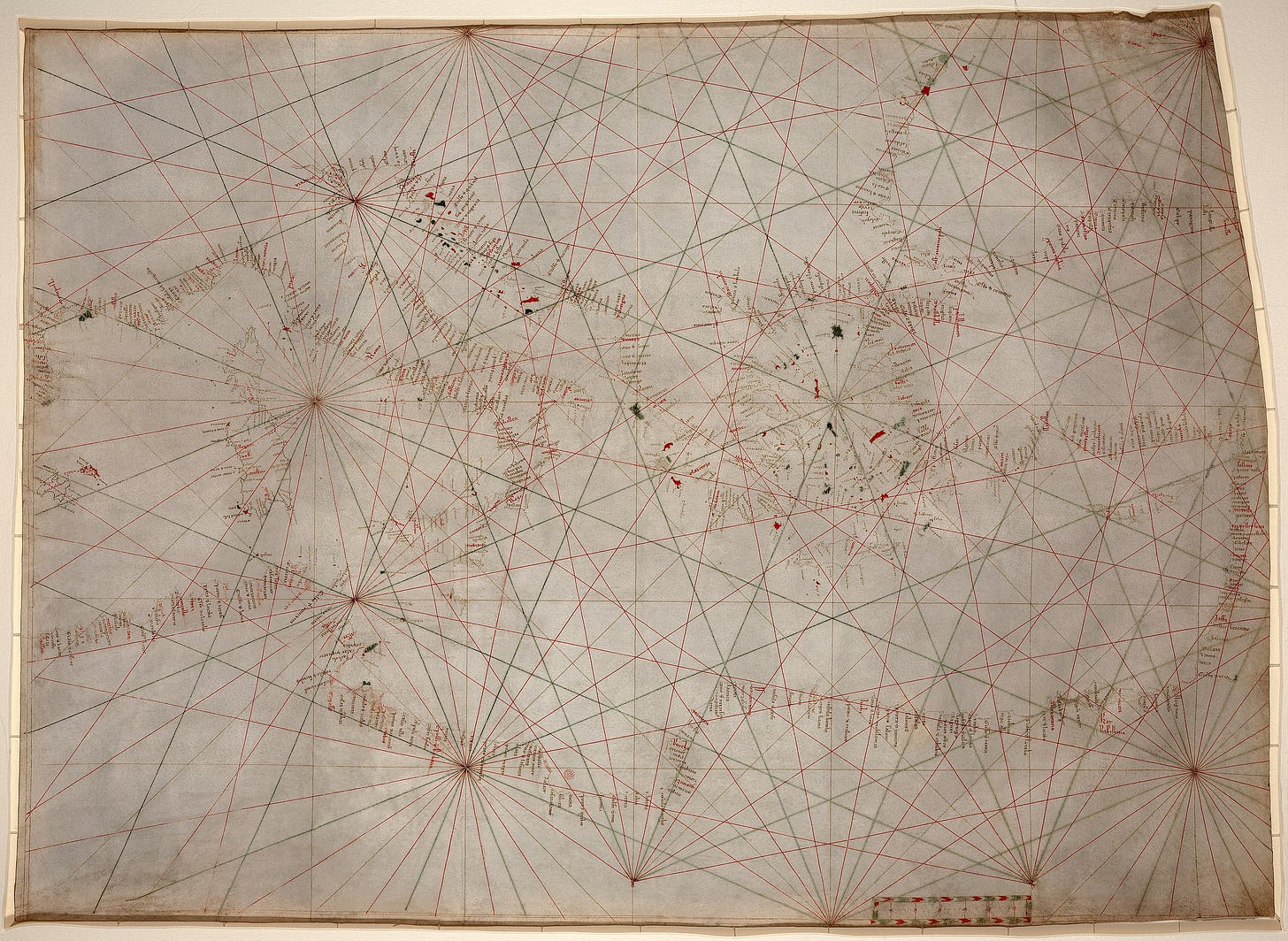

By the late Middle Ages, maps took on a more measured character. This change was largely prompted by trade, especially throughout the Mediterranean, so these early navigational maps are mostly nautical charts. The accuracy of the maps was aided by navigational instruments, including the magnetic compass and the astrolabe, which became available in the late Middle Ages through Mediterranean trade routes.

Florence in particular reached new levels of precision around 1400 when the city rediscovered Ptolemy’s Geographia, originally written around 150 AD. The Ptolemaic style of maps was plainly different from the prevailing model of maps from the earlier Middle Ages. Ptolemy rendered the globe through a consistent system of longitude and latitude coordinates, which gave cartographers unchanging reference points for physical space. And here we have another grid — latitude and longitude lines comprise a coordinate system overlaying the Earth!

If you’re already projecting a three-dimensional globe onto a flat piece of paper, linear perspective is not too unfathomable. The influence of Ptolemaic maps permeated Florence, including the intellectual circles of Brunelleschi and Alberti.67 By the fifteenth century, Florentines were already accustomed to thinking of physical space as something that could be measured and replicated on a two-dimensional surface.

Painting in grids

To illustrate the extent to which Renaissance Florentines were thinking about grids, Alberti created an artistic tool in the shape of a grid. Alberti’s veil, as it is sometimes called, was like the Renaissance version of a Photoshop grid overlay. The invention is simple — a grid is composed of evenly-spaced threads wrapped over a frame, and a matching grid is placed over the artist's canvas.

Alberti’s veil allowed an artist to imitate the shape of objects by painting along uniform gridlines. Painting did not have to be a matter of intuition or eyeballing, as a scene could be projected onto a clearly delineated coordinate plane. Alberti’s veil was not just a technical tool — it also accustomed the artist to think about visualizing the world on a two-dimensional surface.8

These various tools — land surveys, maps, Alberti’s veil — cemented the flat, grid construction in the mind of the painter. When Alberti was writing his perspective manual, he perceived space as consistent, measurable, and modular. As a result, intuition and subjective impression became less important compared to adhering to an abstract system overlayed over physical space.

Glass and mirrors

In addition to thinking of a painting as cells within a grid, Alberti compared it to the view of a scene through a glass window. For him, a painting should be like a crystal clear plane of glass — a flat surface which impeccably imitates three-dimensional space.

Transparent glass is actually a pretty recent invention. The first glass was probably produced around 4,000 years ago in ancient Egypt or Mesopotamia, but it didn’t look much like the glass we see today. Compared to the colorless translucence of modern glass, the quality of glass in antiquity was relatively poor. Due to the lack of high-quality materials and grinding techniques, glass and mirrors were uneven and cloudy. This obscurity of glass was poetically expressed in Corinthians 1:13 — “for now we see through a glass, darkly.”

But by the late Middle Ages, glass began to look much more like the smooth, clear material we’re familiar with. Venice was the global forerunner of glass production — the local sands of were high in silica, and Mediterranean trade routes enabled the importation of high purity soda ash. By the late 13th century, Venetian glass was clear enough that the first eyeglasses were mentioned in northern Italy.9

Glass was a favorite metaphor among Renaissance artists. Leonardo compared glass to the practice of perspective, writing that “perspective is nothing else than the vision of a scene behind a flat and clear glass on which we mark all objects that are on the other side.”10 In addition to the metaphorical inspiration, Renaissance artists used glass as a perspective tool. Leonardo suggested that students trace over a plane of glass to practice imitating perspective lines.11

If you bond metal to a sheet of glass, you have a mirror. During the Renaissance, Venetian glassmaking guilds also created mirrors with a clarity that surpassed their foggy quality in antiquity. Like a plane of glass, a mirror renders the physical world on a two-dimensional surface. The relationship between mirrors and linear perspective is implied by the mirror held by Brunelleschi when he showed off his painting of the Florence Baptistery in his initial demonstration of linear perspective. His Florentine contemporary Filarete even claimed that that Brunelleschi discovered linear perspective by examining the reflection of a mirror.

If you wish to depict anything by another easier method, take a mirror and hold it up to the thing you want to draw. And look into it, and you will see the contours of things more easily, and thus those things that are nearer to you, and those further away will appear smaller and smaller. And truly, I believe, this is the way that Pippo di Ser Brunellesco found this perspective, which had not been used before.12

Perhaps the Renaissance fascination with mirrors was best articulated by Leonardo when he wrote “the mind of the painter must resemble a mirror.”13

Now, what does it mean for a mind to resemble a mirror? For one, a mirror is a wholly unbiased observer. A mirror does not inflate nor diminish the size of objects based on subjective notions, as was common among ancient and medieval painters. Nor does a mirror coat the colors and shapes of a scene with emotional characteristics that are not physically present, as an impressionist painter might. To resemble a mirror, a linear perspective painter seeks to replicate a scene as it concretely appears — nothing more, nothing less.

This attitude requires a fair amount of emotional detachment — the painter must push aside any temptation to paint a shape that does not conform to the linear perspective construction. Further, the artist creates a mental layer of separation between the appearance of a place and the experience of being there. Looking in a mirror or looking through a glass window does this in a literal sense — it separates the viewer from being somewhere while the appearance of the place is fully visible.

Then, Brunelleschi and Alberti did not need to invent a wholly new type of style — they just need to translate what was already seen in glass.

Florentine Philosophy

The Renaissance fascination with glass and mirrors reflected a deeper attitude that Florentines held toward the physical world.

In the early Middle Ages, material things were held with a fair dose of skepticism. To the prevailing Neoplatonist school of the early Middle Ages, the changing and unstable material world was seen as an inferior imitation of the eternal world of Forms. Senses were not trusted to understand reality, as real truth was imperceptible by any sense. In Plato’s Timaeus, one of the few ancient philosophical texts that survived into the early Middle Ages, sensory perception is described as a “dreamlike sense” which allows us to only observe a “fleeting shadow” of greater truths.14

In light of this, we can assume that the "unrealistic" style of medieval art was a deliberate choice. People were trying to escape the material world, not embrace it! This attitude was held by the twelfth century Abbot Suger, who was responsible for rebuilding the Gothic style Basilica of Saint-Denis. He described the aesthetic experience of the “house of God” as transporting oneself from the material to the immaterial world — from the “slime of the earth” to a higher sphere.

I see myself dwelling, as it were, in some strange region of the universe which neither exists entirely in the slime of the earth nor entirely in the purity of Heaven; and that, by the grace of God, I can be transported from this inferior to that higher world in an analogical manner.15

Scholars of the later Middle Ages, particularly among the Oxford Franciscans, were more sympathetic to the material world as a rich source of truth rather than a largely corrupted imitation of higher realities. The revival of Aristotelian texts drew emphasis away from the abstract Platonic Forms and toward direct observation. This went so far as the nominalism of William of Ockham, which denied Forms entirely, and Roger Bacon’s maxim sine experientia nihil sufficienter sciri potest (“without experience nothing can be sufficiently known”).

Late medieval universities supported steady flow of knowledge throughout Western Europe, including the northern Italian university cities of Bologna and Padua. Philosophers like Blasius of Parma dispersed the ideas of Oxford and Paris into Italy, where they were warmly received by Renaissance autodidacts. By the fifteenth century, Florence was immersed in philosophies claiming the credibility of the senses — particular human eyes — to understand the material world.

Florentine Society

So far, I’ve discussed a number of likely contributors to linear perspective — geometry, optics, Ptolemaic maps, transparent glass, and late medieval philosophy. Due to Florence’s role as a wealthy mercantile city, these innovations met at a dynamic crossroads. Florence imported luxury goods through its extensive trade routes while wealthy families funded libraries and academies for reviving classical texts. Though Florence was not a large city by today’s standards, it played the role of a 15th century Silicon Valley, attracting talented artisans, merchants, and intellectuals from throughout Italy.

In terms of the fox-hedgehog dichotomy, Renaissance art is a clear example of the skill of the fox.16 Both Brunelleschi and Alberti were the epitome of Renaissance men. They were interested in many fields outside of painting, and were keen to take advantage of novel tools in their practice. They synthesized the fruits of Florentine innovation and channelled them through a style of painting that had only been hinted at in the Middle Ages.

I think it’s also interesting how painters generally came from artisan backgrounds rather than aristocratic families. Many, if not most, Renaissance Florentine artists began as goldsmiths.17 Working in metalwork would have likely honed their skills in draughtsmanship, metal inlay painting, and practical knowledge of geometry. Before Brunelleschi painted the Florence Baptistery, he already had extensive experience with casting intricate three-dimensional shapes in bronze.1819 Later when he learned Euclidian geometry through Florentine intellectual circles, he was learning a formal version of concepts he already been acquainted with through practical experience.

Along with the talent of Florentine craftsmen, the city had a growing interest in directly observing reality. For most of the Middle Ages, artists did not paint their subjects from life, or en plein air. Rather, they usually painted either from memory or by tracing images from a pattern-book — a compilation of illustrated images of common objects. As a result, people and objects in medieval art often looked relatively indistinguishable from one another.

From the point of view of the typical medieval artist, imitating the material world was not the ultimate goal. But during the Renaissance, it became standard for artists to paint directly in front of their subjects, where they could pay keen attention to the subtle angles, highlights, and shadows of nature.

Florentine painting was driven by this interplay between methodical planning and close observation.20 Perspective artists saw canvases as geometric grids for the artist to loyally depict the colors and shapes visible before his eyes. The perspective lines created the structural outline and the artists’s choice of paints and brushstrokes brought that outline to life.

From the 15th century until the 19th century, linear perspective reigned as the standard method of Western painting. In the pursuit of naturalism, artists embraced a style that was literal, clear, and legible. But why did they stop? Painters after perspective, beginning with the impressionists and ultimately leading to the modernists and post-modernists, viewed the purpose of art differently.

What are the limitations of linear perspective? Is it truly the most realistic style of art?

I will explore these questions in a future essay.

A 1427 Florentine population survey counted 60,000 households, with a total of 260,000 people, or around the modern population of Toledo, Ohio.

English, Edward. A Companion to the Medieval World, 2009. p. 188.

Stanislawski, Dan. "The Origin and Spread of the Grid-Pattern Town." Geographical Review, vol. 36, no. 1, 1946, doi.org/10.2307/211076.

Cataldi, Giancarlo. "Florence: The Geometry of Urban Form." Dipartimento di Architettura, Università di Firenze, revised version received 23 March 2017.

Edgerton, Samuel. Renaissance Rediscovery of Linear Perspective, 1976. p. 114.

Maier, Jessica. Rome Measured and Imagined: Early Modern Maps of the Eternal City, 2016. p. 26.

Schwab, Maren Elisabeth. "Rome as 'Part of the Heavens'? Leon Battista Alberti’s Descriptio urbis Romae (ca. 1450) and Ptolemy’s Almagest." Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 84, no. 1, Jan. 2023, pp. 1-27. University of Pennsylvania Press, doi:10.1353/jhi.2023.0000.

Edgerton, 1976, p. 120-121.

Smith, Barry. "True Grid." Spatial Information Theory: Foundations of Geographic Information Science, edited by D. Montello, vol. 2205, Springer, 2001.

Rasmussen, S. C. (2019). A Brief History of Early Silica Glass: Impact on Science and Society. Substantia, 3(2), 125–138. https://doi.org/10.13128/Substantia-267.

Richter, J. P. The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci, #83, vol. 1, 1970.

As Leonardo eccentrically explained,

Have a piece of glass as large as a half sheet of royal folio paper and set thus firmly in front of your eyes that is, between your eye and the thing you want to draw; then place yourself at a distance of 2/3 of a braccia from the glass fixing your head with a machine in such a way that you cannot move it at all. Then shut or entirely cover one eye and with a brush or red chalk draw upon the glass that which you see beyond it; then trace it on paper from the glass, afterwards transfer it onto good paper, and paint it if you like, carefully attending to the arial perspective.

Richter, J. P. The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci, #523, vol. 1, 1970.

Filarete, Antonio Averlino detto il, Trattato di architettura (1461). Testo a cura di Anna Maria Finoli e Liliana Grassi. Introduzione e note di Liliana Grassi. Milano, Il polifilo, 1972, XXIII, p. 653, 656. https://redi.imss.fi.it/inventions/index.php/Mirror.

Richter, J. P. The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci, #506, vol. 1, 1970.

Plato. Timaeus. Translated by Benjamin Jowett, The Internet Classics Archive, MIT, https://classics.mit.edu/Plato/timaeus.html.

"Abbot Suger." Mapping Gothic: Columbia University and Vassar College, https://projects.mcah.columbia.edu/medieval-architecture/htm/ms/ma_ms_gloss_abbot_sugar.htm.

Berlin, Isaiah. The Hedgehog and the Fox: An Essay on Tolstoy’s View of History. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1953.

Many Florentine artists started out as goldsmiths or studied with goldsmiths to acquire the necessary technical skills. The list includes Orcagna, Andrea Pisano, Ghiberti, Brunelleschi, Donatello, Michelozzo, Luca della Robbia, Cellini, Antonio Pollaiuolo, Verrocchio (Leonardo’s teacher), Leonardo, Ghirlandaio (Michelangelo’s teacher), Bot- ticelli, Andrea del Sarto, and Vasari. If we include those who studied with a goldsmith (Michelangelo) or whose father was a goldsmith (Raphael), we nearly exhaust the roster of prominent Florentine artists. Later and further north, the goldsmith’s trade provided a breeding ground for German Renaissance artists, including Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein.

Cowen, Tyler. In Praise of Commercial Culture, 1998. p. 87.

Renaissance artists tended to come from merchant and commercial families rather than from the nobility. In a sample of 136 Italian artists from the years 1420–1540, ninety-six were the sons of artisans or shopkeepers. Writers, who did not have a well-developed market and required independent support from patrons or family wealth, were far more likely to come from the secure homes of the nobility.

Cowen, 1998, p. 87.

Pimlott, John W. New attitudes toward the drawing and the sketch in the Renaissance and Post-Renaissance Periods, 1961. p. 19.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that Galileo was born in Florence in the century following the invention of perspective painting.